The Geometry of Thought: An Early Exploration in Structured Representation

Can we force a model to think in a more structured, geometric way?

A standard deep learning model learns to represent data in a high-dimensional, unstructured latent space—a chaotic filing cabinet. It works, but it’s a black box. This raises a fundamental question: can we impose a deeper mathematical structure on a model’s internal “thoughts” to make them more interpretable and consistent?

This question led to my first independent research project, undertaken out of my own interest in the intersection of pure mathematics and machine learning.

Instead of looking to statistics for the answer, we turned to a deeper source of structure: algebraic number theory. We hypothesized that the relationships governing quadratic forms, as described by Manjul Bhargava’s work on integer cubes, could serve as a novel form of architectural regularization for a neural network.

The goal was to build a system from first principles. We designed a differentiable loss function that operated independently of the main classification task. Its sole purpose was to penalize the model for creating mathematically inconsistent internal representations. We were testing if we could teach a machine not just what to think, but how its thoughts should be structured.

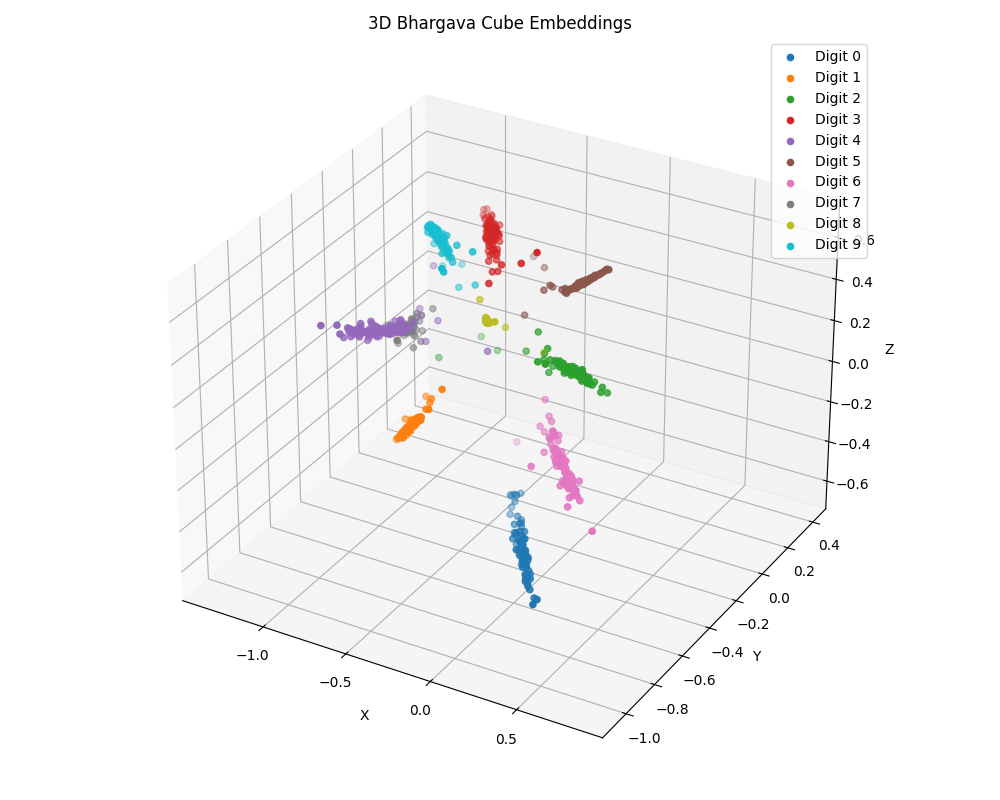

The experiment yielded a clear result on the MNIST benchmark. While the model achieved a high accuracy of 99.46%, the primary outcome was the structure of the latent space itself.

As the visualization shows, the latent space is no longer an unstructured cloud. The embeddings have been organized into a distinct, clustered structure, a direct emergent consequence of the algebraic priors we imposed.

The Key Lesson: From Novelty to Rigor

While this project achieved its proof-of-concept goals, its most valuable outcome was the lesson it taught me about the distinction between theoretical novelty and impactful research. It made me understand that a clever idea validated on a controlled, “toy” benchmark like MNIST is only the first step. True progress requires building systems that are not just elegant, but are also scalable and rigorously validated on complex, large-scale problems.

This realization was the direct catalyst for my subsequent work. It now drives my research into [Artemis, a new class of optimizer] designed for superior performance on challenging, real-world tasks.

This early study taught me that the goal isn’t just to build machines with beautiful internal structure, but to ensure that structure translates into verifiable gains in robustness and generalization where it matters most.

To formalize this independent work, a paper was drafted and submitted for peer review. The process yielded invaluable feedback, highlighting several avenues for significant improvement—particularly the need for more rigorous, large-scale validation. Based on this expert critique, the paper was withdrawn to allow for the comprehensive rework it deserves.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: